1. What is a Trademark?

A trademark in its simplest form is a word, phrase, logo.

Whether you realize it or not, you are interacting with trademarks in almost every single minute of your day.

Have you been on your iPhone lately? The name iPhone is a trademark registered by Apple, Inc.

Perhaps you logged into Instagram while on your iPhone? The name Instagram is a trademark registered by Facebook (now Meta, Inc.).

How about those Nikes you are rocking? The swoosh? The phrase JUST DO IT. Those are trademarks registered by Nike.

Just about every single product or service that you interact with on a daily basis has a name, logo and slogan. And every single one of those is likely registered with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (the “USPTO” for short).

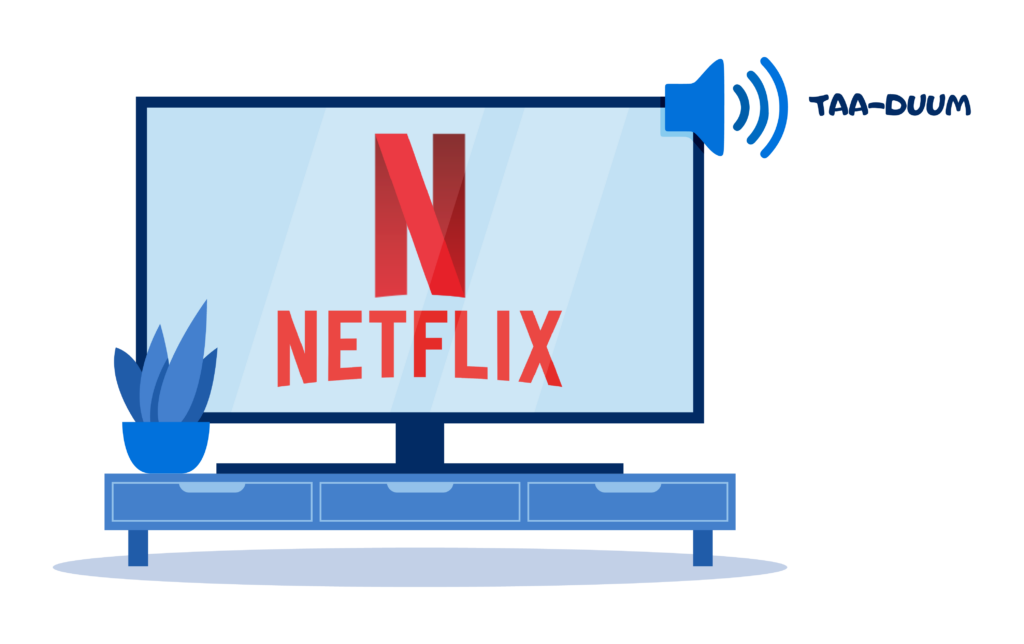

That said, trademarks can also be things such as sounds.

You may feel excited or know your day is ending when the “taduuum” plays while opening up Netflix. That sound is a trademark that was registered by Netflix.

Legally speaking, a trademark is a “source identifier.” This means that a trademark is anything that consumers use to connect the products and/or services they are using with the source of those products and/or services. If you are opening or running a business, obtaining a trademark registrations around your branding can help ensure that you are unique in the marketplace and that consumers can find and recognize your products and/or services easily.

Trademarks are a form of intellectual property (commonly referred to as “IP”). This type of property is considering “intangible.” This means you can not actually hold it. But it is still property that you own. Intellectual property stems from your (protection of actual inventions) and copyrights (works of art). This particular guide covers just trademarks.

2. Most Common Types of Trademarks

A trademark is a distinctive word, symbol, or device that represents a brand and the products or services it provides. Under U.S. trademark law, just about anything can be a trademark, from business names and logos to soundbites. Although trademarks can take a variety of forms, here are the 4 most common types of trademarks and what you should know about each one:

Names

The most commonly used type of trademark is a name (or word) mark. This type of mark may be the name of a brand, or the name of a product or service that a brand provides. To be federally registered, a name trademark must be distinctive. To be distinctive means that when consumers encounter these names in the marketplace, they immediately know the source and quality of the relevant products or services.

A mark’s distinctiveness allows consumers to distinguish a brand from its competitors.

Some of the most well-known distinctive name marks include:

- APPLE for computers

- MCDONALD’S for restaurant services

- COCA-COLA for soft drinks

- BEST BUY for electronics retailing services

- TIDE for laundry detergents

- AMAZON for online retailing services

- NIKE for athletic shoes

- FACEBOOK for social networking services

- CATERPILLAR for construction machinery

- GOOGLE for software for searching online databases and websites

- SHELL for gas station services

- IBM for computers

Logos

Many brand owners also utilize logos, which is why these are one of the most common types of trademarks. Like all trademarks, logos are a short-hand way that brands can communicate to consumers that they are the source/producer of a given commodity or convenience. For instance, when consumers encounter these widely displayed logos, they immediately know the service provider or maker of the good.

Design Mark: an image that utilizes stylized marks, designs, or color.

Examples of popular design marks include:

- Nike Swoosh

- Domino’s Tile

- Target Bullseye

- McDonald’s Arch

- Apple

- Lululemon “A”

- Audi Rings

- Under Armour “UA”

Slogans

Taglines are another method that brands use to distinguish themselves from their competitors. You may not have realized it, but when we hear certain slogans, we inherently associate them with a specific brand.

For example, phrases like “Eat Fresh”, “I’m Loving It”, and “Finger Lickin’ Good” all probably make you think of food, although none of these phrases are inherently synonymous with food. Why is it then that we associate these slogans with food? Well, it’s because these slogans have been consistently used in commercials, radio ads, and billboards in connection with their respective fast-food brand.

Slogans are another commonly used type of trademark.

In fact, we regularly encounter these slogans:

- “Just Do It” for clothing

- “America Runs on Dunkin” for coffee beverages

- “Quicker Picker Upper” for paper towels

- “You Can Do It. We Can Help” for handyman services

- “We Have the Meats” for restaurants

- “Can You Hear Me Now? Good.” for telecom services

- “You’re in Good Hands” for insurance services

- “What’s in Your Wallet?” for credit card services

- “That Was Easy” for office supply stores

- “Taste the Rainbow” for candy

- “Shave Time. Shave Money” for online shaving product ordering services

- “Every Kiss Begins With Kay” for jewelry stores

- “The Happiest Place on Earth” for amusement parks

Sounds

Sounds, including, songs, jingles, and noises are among the most common types. Although sound marks are less commonplace than wordmarks, logos, or slogans, brands regularly use sounds to differentiate themselves from competitors. To register a sound mark, the USPTO requires proof that when consumers hear a certain distinctive sound, they associate it with a particular brand.

Some of the most recognizable sound marks are:

- Homer Simpson’s “D’OH!”

- Netflix’s startup music

- AOL’s “You’ve Got Mail”

- Aflac’s duck quacking the word “AFLAC”

- Yahoo’s “YAHOO” yodel

- The Pillsbury Doughboy Giggle

- Red Robin’s “RED ROBIN, YUMMM”

- Taco Bell’s “BONG”

- Darth Vader’s Breathing

- Tarzan’s yell

- ESPN’s intro music

- MGM’s lion roaring

- Intel’s startup music

- NBC’s Chimes

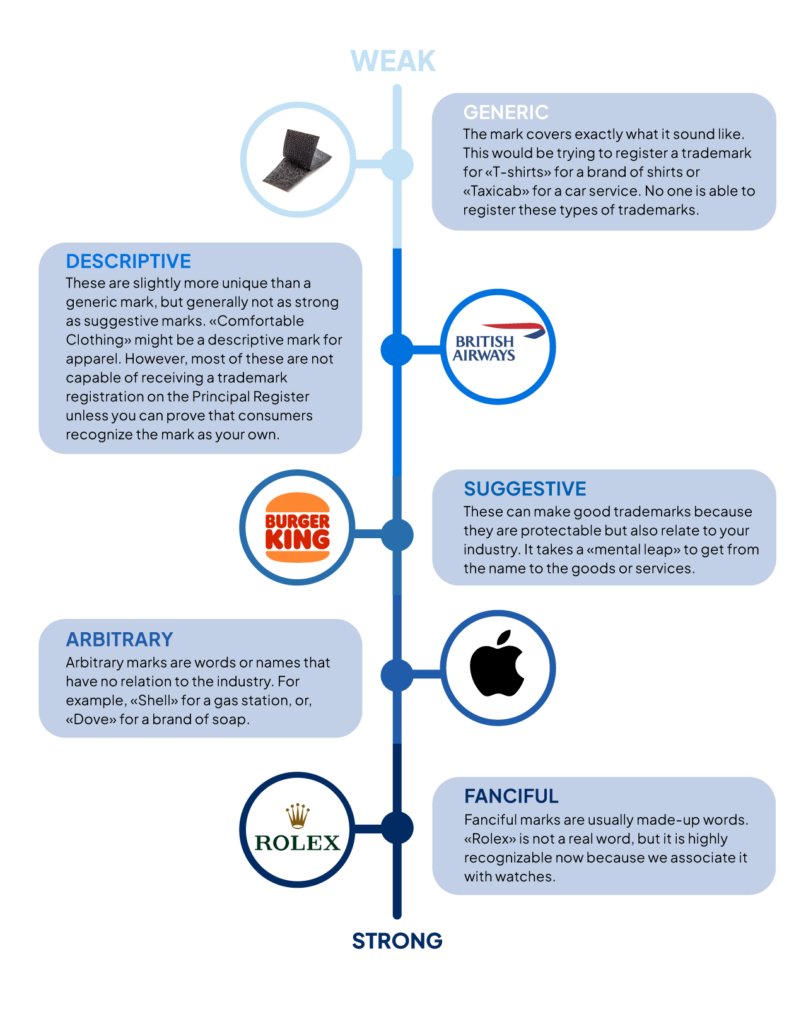

3. How to Select a Strong Trademark

It is very important to know that not all trademarks are created equal. In fact, trademarks come on a sliding scale of protectability.

Here is how that scale works, from the most protectable to the least protectable:

Arbitrary / Fanciful:

Names that have virtually no meaning in relation to the goods and services they’re used in connection with. Arbitrary names are inherently distinctive and tend to offer brand owners the best chance of successfully registering their names.

These are the two strongest trademark types. Arbitrary marks are words or names that have no relation to the industry. For example, “Shell” for a gas station, or, “Dove” for a brand of soap

Fanciful marks are usually made-up words. “Rolex” is not a real word, but it is highly recognizable now because we associate it with watches. If not for strong advertising, these marks would have no consumer recognition.

Suggestive:

Names that give consumers a hint about the nature of goods or services, but require consumers to use their imagination to reach a conclusion as to the nature of the goods/services.

These can make good trademarks because they are protectable but also relate to your industry. It takes a “mental leap” to get from the name to the goods or services. “Netflix” is a well-known example. The trademark itself is not “Movie Streaming App,” but it does allow the consumer to understand there are movies (i.e. “flix”) available via the internet (i..e “Net”).

Descriptive:

Names that immediately convey the characteristics of the goods or services. To register a descriptive name the USPTO requires evidence that when consumers encounter the name, they are able to identify a single brand as the source of the product/service. These are slightly more unique than a generic mark, but generally not as strong as suggestive marks.

“Comfortable Clothing” might be a descriptive mark for apparel. However, most of these are not capable of receiving a trademark registration on the Principal Register unless you can prove that consumers recognize the mark as your own. “American Airlines” would be an example of a trademark that has achieved this level of recognition. This is not a recommended branding approach because it can be hard to achieve such popularity.

Generic:

Names that are the popular term for describing a class of products or services. These names are so widely used in connection with a general class of items or services, that they are the only (or most common) term for describing a specific product or service. This would be trying to register a trademark for “T-shirts” for a brand of shirts or “Taxicab” for a car service. No one is able to register these types of trademarks.

Even if you have a strong mark, you need to make sure that your mark is unlike anything else in the market. “Rolex” and “Shell” are strong marks due to their unique nature, but if every gas station was named “Shell,” “Seashell,” and “Beach Shell,” then the point of having a fanciful or arbitrary name is null, and the scope of your protection is limited again.

4. What is a Federal Trademark Registration

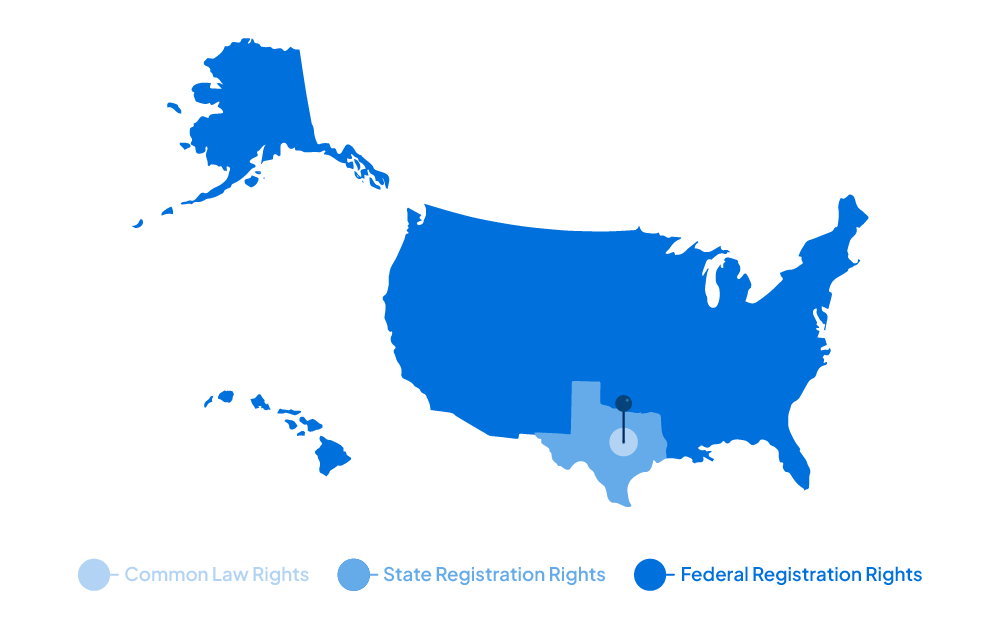

Difference between common law rights, state registration rights, and federal registration rights

Common law trademark rights go to the first company to use the mark. These rights are not federal and cannot be enforced nationwide. For example, a small town store can only enforce its rights in the small town in which it is based.

Common law trademarks are harder to enforce than federal trademarks because there is no “presumption of validity” of the trademark. You have to prove that consumers recognize your trademark sufficiently in order to have earned a trademark right. That said, for some small businesses who can’t afford federal registrations or have no plans of expanding to other areas, they can rely on common law protection in the event a local trademark infringement occurs.

The second type of trademark registration rights can be found at the individual state level. Each of the 50 states have their own state government trademark database. Registering your trademark with an individual state’s database, only affords your trademark protection within that particular state.

Federally registered trademarks are the most secure. A federally registered trademark provides the presumption of nationwide validity in a trademark. It is the most effective method to prevent other companies or individuals anywhere in the United States from using your name on similar goods or services.

Do I need a federally registered trademark to sell products or services?

While you don’t need a registration to begin using a brand (there is no legal requirement that you register a trademark to use a trademark), it is strongly advisable. Once you go through the federal registration process and are granted a trademark registration, it is less likely to be infringing on someone else’s trademark. Additionally, you are better protected in case you have a brand that goes viral or creates big business.

If you don’t go through the federal registration process when you start your business, you also run the risk of finding out that a competitor with a similar name does have a trademark registered. This would force you to change after you have already begun your marketing efforts. Therefore, while it isn’t required to obtain one, if you do plan on getting a federal registration, you should start as soon as possible.

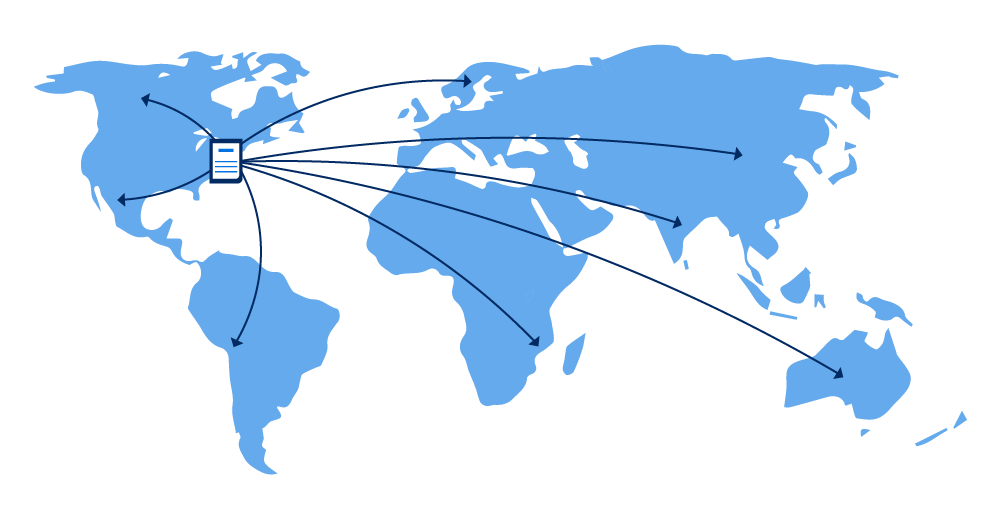

5. International vs. U.S. Based Trademarks

Trademark applications filed with the USPTO only protect the trademark within the United States, even though many businesses operate internationally. If you intend to engage in international business or are worried about counterfeits emanating from another country, consider filing trademarks in other countries to ensure global brand protection.

There are two methods of filing trademark applications in different countries.

- Using the Madrid Protocol (an international system that avoids the need to engage local attorneys).

- Using local attorneys to file individual applications in each country that an applicant would like rights in.

1. Filing Trademarks via the Madrid Protocol for International Protection

While there is no universal international trademark protection, an international treaty called the “Madrid Protocol” attempts to streamline the process. Over 90 countries have signed on to the protocol, including the European Union, China, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Mexico.

To use the Madrid Protocol, you must first file a traditional application in the United States. As soon as that application has been filed, there’s no need to wait for approval before beginning the Madrid Protocol filing process. The process starts by completing one application in the native language, then selecting which countries you want to send their application to.

| Pros to using the Madrid Protocol | Cons to using the Madrid Protocol |

| • It can be cheaper than hiring local counsel in each country. To file under the Madrid Protocol, you will pay one application fee along with a registration fee in each country that you register your mark in. While it can become expensive, it will save individual legal fees and filing fees upfront. | • Madrid Protocol applications cannot vary or be more expansive than the original application. For example, if an application is filed for “shirts” with the USPTO, an applicant cannot file for “purses, hats and shoes” elsewhere since it is considered “outside the scope” of the original application. All of the intended goods and services must be outlined clearly in the original application to avoid limiting the application when filing with the Madrid Protocol. |

| • Navigating a single application in a trademark applicant’s native language is far simpler than attempting to complete applications in foreign languages. Mistakes that can arise from poor or automated translations of complicated forms can become costly if it results in refusals or office actions. | • Applicants have to hire local counsel if any issues arise in the registration process in the country, whether those are identification issues, a likelihood of confusion, disclaimers, or descriptiveness refusals. This can feel overwhelming if a tight deadline or a complicated/expensive response is required. |

| • All Madrid Protocol applications can be updated with one additional filing. For example, if the owner’s address changes, instead of filing 10 different address changes the Madrid Protocol facilitates the process and makes it more efficient to keep trademark portfolios current and accurate. | • A Madrid Protocol application is dependent on successful registration of the United States application. If the home application is unsuccessful because of an Office Action or missed deadline, then the Madrid Protocol application will not register either. |

2. Filing Trademarks via Local Counsel for International Protection

Even though the Madrid Protocol can be a valuable tool for straightforward applications, there still are good reasons to consider hiring local counsel.

| Pros to Hiring Local Counsel | Cons to Hiring Local Counsel |

| • It can streamline the process in each individual country and be the fastest road to registration. | • If there are numerous countries, hiring local counsel in each country can cost much more than a Madrid Protocol application. |

| • The foreign application is not dependent on the United States application being approved. | • Locating reliable local counsel in each country can be difficult, since some attorneys may not have the necessary expertise. |

| • It can be less expensive if there are only a few countries in which you are seeking protection. | • Managing files on each individual foreign application can be an additional administrative strain on applicants and can result in missed deadlines or lapsed applications. |

| • A complicated or nuanced application can require someone fluent in the local language. | |

| • Some countries have different rules than the United States and local counsel will understand how to best protect a trademark in a given country. |

When filing via the Madrid Protocol, many trademark owners located outside of the United States will ultimately have to engage a local U.S. trademark attorney to respond to an issue with an application. Often, the U.S. trademark attorney may suggest filing a new application to ensure compliance with USPTO requirements. This convoluted process can result in a loss of priority and additional costs.

International trademark registrations are becoming more necessary in an increasingly global world. You should seek the appropriate legal counsel to develop the best and most efficient plan for international trademark protection.

6. Principal vs. Supplemental Registers

What are the Registers?

The USPTO holds two “registers,” which are lists where trademarks are stored and advertised.

The Principal Register is stronger, although the Supplemental Register has its own benefits. The Principal Register is reserved for “distinctive” marks. Distinctive marks are marks that have no relationship to their goods or services, such as Shell for gas stations, or made-up words, such as Verizon or Kodak. The Supplemental Register is for marks that are descriptive of the goods and services, or less unique, such as American Airlines for air transport of passengers.

Principal vs. Supplemental Registers

| Trademarks on the Principal Register: | Trademarks on the Supplemental Register: |

| • Are presumed to be valid in a lawsuit and show presumed ownership. | • Require that owners prove that the trademark is “valid” and that ownership is valid. |

| • Give every infringer “notice” that the owner has rights in the mark, so they cannot claim a good faith defense. | • Do not give infringers constructive notice, so infringers can still claim they were unaware of your trademark rights. |

| • Can be filed as “Intent to Use” to give you an earlier priority date. | • Cannot be filed as “Intent to Use.” |

| • Can become “incontestable” where no one can argue the owner does not have rights if you file a Section 15 declaration. | • Cannot have an incontestable mark. |

| • Both Registers allow you to bring a trademark infringement suit in U.S. Federal Court, allow you to use ®, and are a roadblock to similar marks applying to be on the Registers. | • Both Registers allow you to bring a trademark infringement suit in U.S. Federal Court, allow you to use ®, and are a roadblock to similar marks applying to be on the Registers. |

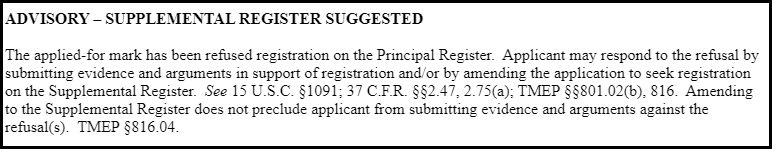

USPTO Can Recommend the Supplemental Register

A mark will end up on the Supplemental Register if the USPTO finds the mark descriptive during its examination. This determination will come in the form of an Office Action, and unless the mark is generic, the examining attorney will make a recommendation to amend to the Supplemental Register.

You can respond to a descriptiveness advisory with arguments of distinctiveness, or can accept the suggestion and amend to the Supplemental Register. One issue with these simple amendments is that Intent to Use applications are not eligible for the Supplemental, so you must immediately prove use if you want to proceed to registration that way.

Moving from Supplemental to Principal Register

The Supplemental Register is not necessarily permanent. Trademark owners can apply to be on the Principal Register after five consecutive years of use, since the mark will have “acquired distinctiveness.” Occasionally, if a mark is deemed highly descriptive by the USPTO, then the refiled application may also be denied based on the date of first use alone.

So how can you prove distinctiveness if the USPTO requires additional evidence? You can provide:

- receipts or invoices from over five years ago;

- proof of advertising expenditures and examples of advertising;

- affidavits from consumers who know or recognize the trademark; or

- surveys of relevant consumers, market research and consumer reaction studies.

Some lesser-known evidence that helps establish distinctiveness, but doesn’t necessarily indicate distinctiveness alone, includes:

- State trademark registrations.

- Design patents.

- An already recognized “family of marks” that this new mark will be joining.

- Parodies and copies of the mark.

- Acquiescence of competitors to not use the mark in the relevant space.

After an applicant’s refiling is considered, and if they make it onto the Principal Register, the applicant typically allows the Supplemental Registration to lapse, and the applicant now has a stronger registered mark.

Comparison of the Principal and Supplemental Registers

| PRINCIPLE REGISTER | SUPPLEMENTAL REGISTER | |

|---|---|---|

| Registrant may use the ® notice symbol with the trademark |

|

|

| Eligible for enrollment in Amazon's Brand Registry program |

|

|

| Eligible for recordal with U.S. Customs |

|

|

| Presumption of national validity of the trademark registration |

|

|

| Strong ability to enforce the trademark against infringers |

|

|

| Can receive incontestability status after 5 years of registration |

|

7. Why Obtaining a Trademark Registration is Important

A trademark registration is paramount for trademark owners — it provides enhanced protection for a brand throughout the United States and shows an investment in the long-term quality and value of the brand. A registered trademark is an important asset for the reputational, developmental, and competitive schemes of every brand.

The importance of Trademark Registration

- Public Notice of your Trademark

A registered trademark is a visible representation of brand ownership. Only a registered trademark can be denoted by using the Circle R (®) symbol, while an unregistered trademark is indicated by using the letters TM.

Trademark registration also establishes your brand’s reputation and signals to consumers that the products or services tied to your trademark meet your brand’s quality and control standards. It is a shorthand that helps consumers make purchasing decisions by enabling them to easily identify and distinguish your goods or services from those of your competitors.

A federally registered trademark also provides “constructive notice” to would-be infringers. Under federal trademark law, the date your application is filed is the “priority date,” or the effective date of your trademark rights. As of this date, everyone in the United States has constructive notice of your trademark ownership. If someone uses your mark, they may be liable to you for trademark infringement even if they have never heard of your brand. - Nationwide Presumption of Validity and Ownership

A trademark registration is applicable nationwide and provides a presumption of your trademark’s validity and your ownership of the mark. Under federal trademark law, every registered trademark is presumed to have satisfied all the USPTO’s substantive requirements for registration and rightfully belong to the owner of the trademark registration.

These presumptions enable you to expand your business into any U.S. locale with the confidence that your trademark will be protected there and without the fear of trademark infringement. They also provide an upper hand in litigation and disputes involving your trademark by saving you the time and expense of proving that the trademark is validly registered or rightfully owned by you. - Deterrence Against Infringement of your Trademark

A trademark registration is a legal shield for your brand. It discourages competitors from infringing on your trademark and gives you the ability to police how your mark is used. You can demand that infringers stop using your mark, and appeal to social media providers and online marketplaces to remove infringing content. You may also request that U.S. customs officials prevent counterfeits of your products from entering the country. View this blog post for more on U.S. Customs and brand protection.

Another benefit of registration is that your trademark is added to the database of registered trademarks. This means that anyone conducting a trademark search will come across your trademark and be dissuaded from using it or a similar mark.

Trademark registration establishes ownership of a brand’s name, slogan, or logo and provides protections against infringement. While obtaining a trademark registration may seem overwhelming, it is an important asset for the overall development and continuity of any brand. If you are unsure of how to obtain a trademark registration or how to take advantage of the full scope of rights conferred by your existing trademark registration, please contact an experienced trademark attorney at Gerben IP.

8. Should I Hire an Attorney or Can I Register a Trademark Myself?

If you are a U.S. citizen or company with a U.S. domicile, you can register a trademark without the assistance of an attorney. However, you should know that registration is a rewarding, yet complicated process that requires precision and accuracy every step of the way. Hiring an experienced attorney will give you the best chance of successfully registering your mark.

You Can Register a Trademark Yourself

Many individuals and business owners believe that registering a trademark themselves is more cost-effective and efficient than hiring an attorney. However, this assumption doesn’t take into account the potential pitfalls and consequences of filing an application without professional assistance.

Trademark applications are complex documents, loaded with legal terminology and technicalities. The substantive requirements of these documents must be rigidly followed because just one mistake or omission in the initial application can cause the USPTO to refuse to register your mark.

Failure to adhere to these documents’ substantive requirements may also cause the USPTO to request additional documents and information before allowing your application to proceed to registration. This can significantly increase the costs of registration and prolong the process.

In the long run, clerical errors due to inexperience can be detrimental to your application and require the hiring of an attorney to fix errors or refile an application — both of which can end up costing more than hiring an attorney from the beginning.

Perks of Hiring an Attorney

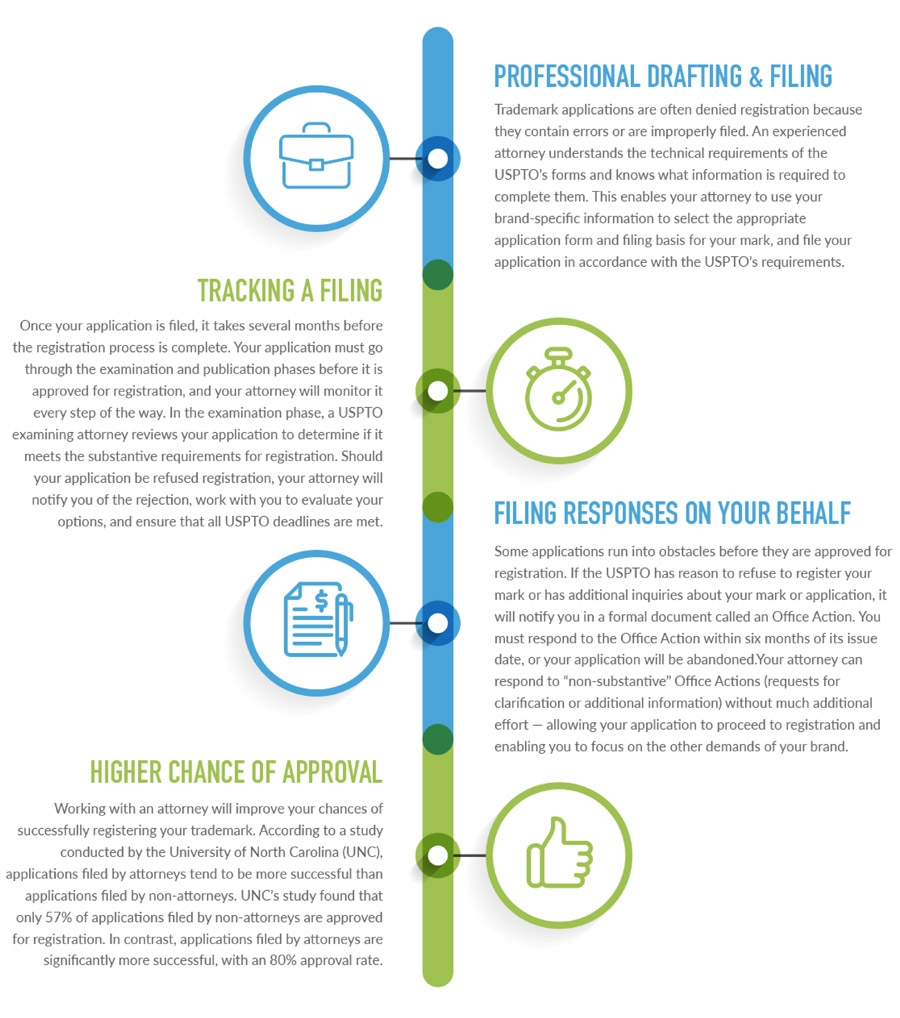

Working with a specialized attorney who routinely deals with USPTO filings is more beneficial than doing it alone. There are four main reasons that an attorney adds value to the trademark registration process:

- Professional drafting and filing

Trademark applications are often denied registration because they contain errors or are improperly filed. An experienced attorney understands the technical requirements of the USPTO’s forms and knows what information is required to complete them. This enables your attorney to use your brand-specific information to select the appropriate application form and filing basis for your mark, and file your application in accordance with the USPTO’s requirements. - Tracking a Filing

Once your application is filed, it takes several months before the registration process is complete. Your application must go through the examination and publication phases before it is approved for registration, and your attorney will monitor it every step of the way.In the examination phase, a USPTO examining attorney reviews your application to determine if it meets the substantive requirements for registration. Should your application be refused registration, your attorney will notify you of the rejection, work with you to evaluate your options, and ensure that all USPTO deadlines are met.

If your application is approved at the examination phase, or if your attorney successfully overcame the initial rejection, your application will proceed to publication – meaning it is listed in the USPTO’s official publication, which gives the public notice of your intent to register your mark.From start to finish, your attorney will follow the application and provide status updates as it advances through the registration process. - Filing responses on your behalf

Some applications run into obstacles before they are approved for registration. If the USPTO has reason to refuse to register your mark or has additional inquiries about your mark or application, it will notify you in a formal document called an Office Action. You must respond to the Office Action within three months of its issue date, or your application will be abandoned.

Your attorney can respond to “non-substantive” Office Actions (requests for clarification or additional information) without much additional effort — allowing your application to proceed to registration and enabling you to focus on the other demands of your brand. - Higher chance of approval

Working with an attorney will improve your chances of successfully registering your trademark. According to a study conducted by the University of North Carolina (UNC), applications filed by attorneys tend to be more successful than applications filed by non-attorneys. UNC’s study found that only 57% of applications filed by non-attorneys are approved for registration. In contrast, applications filed by attorneys are significantly more successful, with an 80% approval rate.

While you can register a trademark by yourself, utilizing an attorney will make a significant difference in the process and outcome. An attorney’s assistance can help you avoid drafting and filing mistakes, manage deadlines, respond to subsequent USPTO requests, and — most importantly — increase your trademark’s chances of registration.

9. How Much Does It Cost to Federally Register a Trademark?

Filing a trademark with the USPTO can seem like an expensive process when combined with legal fees charged by your attorney. However, it can save thousands in legal fees in the long run.

Government Filing Fees

- How to Determine Filing Fees

Trademark applications are broken down into “classes” of goods and services on which the trademark will be used. These classes are based on an international classification of goods (the “Nice Classification”) used around the world to group types of goods together that are related in the market. For example, Apple, at its most broad, would cover cell phones, smartwatches, and desktop computers (Class 9), but also retail stores (Class 35) and repair of cell phone hardware and software (Class 37 and Class 42). Understanding which classes are essential affects the cost of a trademark application because the USPTO charges per class. - Filing Fees

Each class the trademark will cover can cost between $250-$350 to file. The lower rate is if the language is all pre-approved by the USPTO, which can occur if the goods and services are typical (clothing, general merchandise, retail services, etc.). However, if you provide complicated or novel services, it might be best to use the $350 rate to describe what the trademark will cover most accurately. - In Use

The most straightforward path to registration is an “In Use” application. This application is when you are already selling the goods or providing the services you intend to trademark. An In Use application is also a cheaper option since the applicant only pays the upfront filing fees. - Intent to Use

A second filing type is an “Intent to Use” application. These applications are when you intend to use the trademark in commerce but have not yet had sales or customers. The benefit to an Intent to Use application is that the federal priority date will be the date of filing, not the date of first use. Sometimes, applicants want to ensure the name they will be using on their products is not too similar to another and will try to clear the application process before using the mark in commerce.

A downside to this filing strategy is the additional cost. After the USPTO initially clears the name, it will issue a Notice of Allowance, which is a six-month period where you will provide proof of use, or proof of your trademark in commerce. There are two choices at the end of this first six-month period: You can either file proof of use in commerce, which will cost $100 per class, or file an extension. Extensions are $125 per class, and you can file up to six extensions, essentially giving you three years to get the brands off the ground.

Intent to Use applications can be costly if you need to file all available extensions in multiple classes. Still, the earlier priority date and name security can potentially save thousands in rebranding costs later.

Cost for Assistance from Experienced Trademark Counsel

- Legal Costs for Experienced Trademark Counsel

When searching for trademark counsel, you’ll encounter offers of “fast & easy” filing assistance for less than $100. These advertisements can be misleading because they don’t include the USPTO fees, any clearance search, and any additional responses the USPTO may require before issuing a registration. On the contrary, some attorneys will charge hourly rates for trademark searches and filings, which can cost up to $5000 or more depending on the amount of counseling an applicant will need through the filing process. - Gerben IP’s Fees

To increase transparency in fees, we offer a flat fee search and filing for $1,500. Our search includes the federal register, state registers, and the common law marketplace to ensure that your unique name isn’t being used elsewhere in the country and to accurately gauge the risk of your trademark filing.

Additionally, our flat fee covers:- Calls with an experienced attorney to discuss the search results or searches conducted to understand the risks better.

- Counseling before filing (what constitutes proof of use, which filing method is best for your application, and any questions that may arise for first-time trademark filers).

- Tracking your application through the USPTO and providing updates each time we receive them.

We also cover any non-substantive Office Actions that the USPTO may issue. For example, the USPTO might ask to clarify goods and services, provide a domicile address, or disclaim a word. We will follow the trademark application through these processes for no additional cost.

- Some trademark applications will face more serious issues. Still, those are issues that we typically warn applicants about beforehand, and we will always inform you of the fees associated with these responses before charging you.

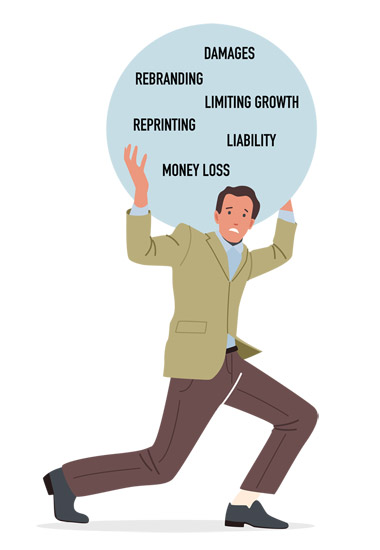

Cost of Not Having a Trademark Registration

It may seem that a trademark application is costly, and even then, may not result in trademark registration. However, it is essential to understand the cost of not having a registration.

- If the brand is too similar to another brand, you could have to pay the cost of rebranding.

Suppose that an applicant starts a brand that is the same or too close to the name of a business with a federally registered trademark name. In that case, the person with fewer rights who began the brand later often has to choose between costly litigation or costly rebranding. Litigation is complicated because the business owner is already in a weaker negotiating position, so newer businesses will often choose to rebrand.

Rebranding an existing business is difficult not only because a business must create all new branded materials, but also sometimes destroy all existing materials they have already printed. This can include advertising materials, decorations, and online presence such as domain names and web design. The business also loses the goodwill they have built up in the name, which can often drastically affect its value. - If the brand is too similar to another brand, business owners can become personally liable for their common law trademarks.

If you want to pursue litigation and damages against another business that uses a confusingly similar name, the infringing business may be personally liable for damages. Business entities usually own federally registered trademarks to limit personal liability, but some common law trademarks are recorded under the individual rather than the business. If a business owner is personally advertising their business with an infringing name, the individual could be personally liable for lost profits and any other damages. - Not having a federal trademark registration can limit the potential growth of a brand.

While it may not cost you money, common law trademark rights may inhibit growth. Investors look for savvy business owners, and one way to show that is to protect intellectual property. A trademark portfolio shows investors that the brand is valuable and well-protected or monitored.

Additionally, a trademark portfolio allows for easier and more clear licensing deals, which provides the potential to grow your brand. Finally, federally registered trademarks are nationally protected, while common law rights are limited to the geographic location where they began. This can stunt expansion and be another costly consequence of not registering a trademark.

10. How Long Does It Take to Federally Register a Trademark? (Timeline of the USPTO Process)

It typically takes a year or more to secure a federally registered trademark. Successful registration requires an investment of time and resources. When preparing to register a trademark, you should consider the approximate length of each step of the process so that a budget and strategy can be developed that spans the estimated duration.

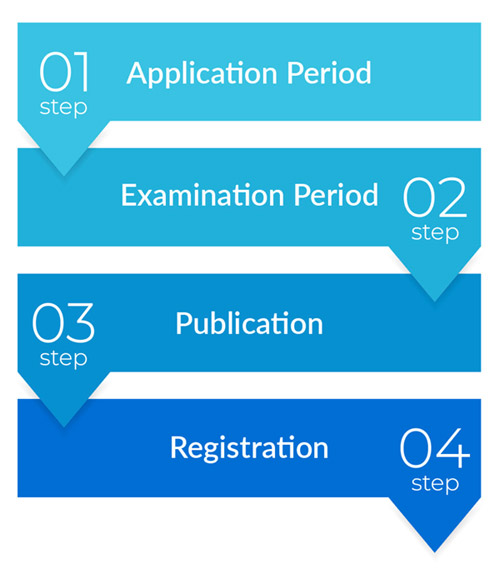

The Registration Process

On average, it takes 12-18 months for a trademark to complete the USPTO registration process. Given this wait time, it’s important to start the registration process as soon as possible. The process even rewards those who start early: Under U.S. trademark law, regardless of when your trademark is approved for registration, you will receive retroactive protection and rights in your mark dating back to your application’s filing date.

Here are the timeframes associated with each phase of the trademark registration process.

- Application Period

The application period refers to the actual drafting and filing of your trademark application. This includes selecting the material you want to federally register; determining the appropriate the appropriate filing basis for your mark; selecting the correct application documents for your mark; completing these documents with your brand’s specific information; and submitting them to the USPTO for review.

As soon as an application is filed, you should receive a serial number to track your application through the USPTO process. At this point, you should start using ™ or a similar identifier after your mark to indicate to others that this is a brand identifier. - Examination Period

Once your application is submitted, it will be assigned to a USPTO examining attorney. The current wait time from filing to examination is approximately eight months. The USPTO has recently brought on additional examining attorneys to combat this. The goal is to examine the mark within six months.The examining attorney will review it for accuracy, and ensure that it satisfies the substantive requirements for registration. The examining attorney will also conduct a conflict check to see if your mark raises any issues with existing trademark registrations.

If the examining attorney finds any reason — such as failure to adhere to the substantive requirements of registration or conflicts with a pre-existing mark — your mark will be initially refused registration. You will receive notice of this refusal through a formal document called an Office Action. You must respond to the Office Action within three months of the date it was issued, or your application will be abandoned.

If your application satisfies the requirements for registration and there are no conflicts with an existing trademark (or you’ve overcome any issues raised in an Office Action), then your application will be initially approved for registration and proceed to publication. - Publication

If your mark has been initially approved for registration, the USPTO will issue what is known as a Notice of Allowance, letting you know that your mark successfully completed the examination phase.Within 30-60 days of issuing your Notice of Allowance, the USPTO will announce your mark in its official publication, giving the public notice of your intent to register your mark. Publication of your mark also commences a 30-day period in which any party that believes your mark conflicts with its own mark can object to the registration of your mark. - Registration

If there are no objections to the registration of your mark within the allotted 30-day period, the USPTO will issue your registration certificate – officially concluding the registration process.

Can You Expedite the Process?

The registration process can be made significantly faster by consulting with an experienced trademark attorney. An attorney will prepare and file your application in accordance with the USPTO’s requirements, reducing the margin for error in the application phase and decreasing the chances that your mark will be refused registration in the examination phase.

An attorney will also conduct a comprehensive clearance search to assess the likelihood that your mark will be approved for registration and whether it conflicts with existing trademark registrations. This search will enable you select a unique trademark, reducing the likelihood that a third party will object to the registration of your mark in the publication phase.

11. Decisions to Make Before Filing an Application

Here are some things you should do before filing your trademark application that will make the process easier, and help avoid any potential obstacles.

- Determine Ownership

Although you can file for trademark registration by yourself, the question of who will actually own the trademark is one of the first decisions you’ll have to make. Naming the proper owner in the application is critical to obtaining and maintaining a valid trademark. Guidance from an experienced attorney can be invaluable.

If you choose to register a trademark in your own name, it could potentially leave you open to personal liability in some cases. It would also be difficult and costly to correct if a business entity is created and the trademark rights need to be transferred.

However, most applicants choose to shield themselves individually and take advantage of trademark ownership benefits through an LLC, corporation, or other formal business entity. - Description of Goods and Services

Trademarks don’t cover every single good or service in the marketplace, but only cover the goods and services the applicants intend to provide. For example, the Dove trademark is registered by two different companies — one for soap and the other for chocolate.

Once you have decided what goods or services you intend to provide, they must be categorized into “classes” as specified by the Nice Classification. There are 45 classes, and each one covers a group of items; for example, Class 25 includes apparel, Class 9 includes electronic hardware and downloadable software, and Class 45 includes legal services. Some applicants find this to be the most complicated part of filing a trademark application. - Filing Basis

In Use (1a) – The most straightforward path to registration is to file “In Use.” This means you are currently selling the goods or providing the services listed in the application. A trademark registration requires that each and every good and service listed is available and in use by consumers, so if even one item is not yet being sold, an applicant will have to file as “Intent to Use”.

Intent to Use (1b) – If you are starting or expanding a business, you may not yet have begun selling goods. To ensure priority or intellectual property protection, savvy business owners will file an “Intent to Use” application which states they have a genuine intent to make sales in the United States under that trademark. You may pursue an Intent to Use application to either get a federal priority date earlier than you would with an In Use application, or because you want to clear it through the USPTO before creating branding or advertising materials.

An Intent to Use application also requires an additional filing – the proof of use. Since all trademarked goods and services have to be sold to consumers at the time of registration, the USPTO requires the applicant to sign a legal document stating these are all in use. - Can You File Your Name and Logo in the Same Application?

Yes, your name and logo can be filed together, but it is not always advised. A trademark is meant to be a singular item. If you include your name and your logo in the same application, you’re applying for a single mark that consists of your name combined with your logo, known as a design mark. Before applying for your name and logo together, you should consider the advantages and drawbacks of registering a design mark.

If your application is approved for registration, you’ll have federally enforceable trademark rights for your design mark and for your name and logo as individual components. For example, the mark below is a registered design mark comprised of Nike’s name and logo. This registration protects Nike’s name and logo if either were used by an unauthorized party in an infringing manner.

However, if an unauthorized party were to use Nike’s name and logo in a very different design mark, the rights provided by this registration would be determined by comparing the marks’ “commercial impressions” (their appearance, sound, and meaning). If the two marks are identical, but their designs are vastly different, the third party could argue that because the designs are so unique and distinct, they create different commercial impressions, and therefore is not an infringement of Nike’s trademark rights.

Trademark Registration for Nike’s Name and Logo

Source: https://www.uspto.gov/trademarks/basics/trademark-examples

Moreover, if Nike were to change this logo in the future, then the Registration would no longer be able to be renewed or enforced. As a result, Nike would still have common law trademark rights, but they would not have a trademark registration for this design and would need to reapply to register their revised logo. Ultimately, an application for just words can provide broader protection over the words in the mark – without diluting that protection by tying it to a logo.

12. After Registration

After registration, you still have responsibilities. The USPTO will consider the registered trademarks when considering other trademark applications. However, you still have the responsibility of policing the marketplace and keeping your trademark current to retain your rights.

Maintaining a Trademark Registration

A trademark does not expire like a patent but is instead valid if it is still being used in commerce. However, there are “maintenance” documents that registrants must file to prove to the USPTO that they are still using their trademark properly.

The first maintenance document must be filed between the 5th and 6th year following the registration of the mark. This means if the mark registered on January 30, 2020, the earliest the Registrant can file a renewal is January 30, 2025, and has until January 25, 2026. The USPTO also allows “grace periods” of six months after the last date, but there are additional fees due to the delay.

The next maintenance document is filed between the 9th and 10th year, with the same grace period. After this second renewal, all maintenance documents are due ten years after the previous.

Keeping Ownership Current

In addition to filing maintenance documents, a registrant must continue to ensure the correspondence information, attorney information, and ownership information are accurate. Keeping an accurate record with the USPTO will ensure that deadlines are not missed, and all correspondence will go to the correct parties.

Policing the Marketplace and USPTO Applications

Keeping the uniqueness of a registered trademark is important to keep it as a source identifier for your goods and services. Here are some ways to ensure that other marks do not get registered or stay registered with the USPTO that a registrant believes are fraudulent, are too similar to theirs, or do not have priority.

- Letters of Protest

This letter is filed as soon as an application is filed and asks the USPTO to consider the registered mark when analyzing the protested application. You can sign up for a monitoring service or continuously monitor the USPTO database for words that are believed to infringe on your mark. - Oppositions

As discussed previously, each application goes through a publication period where third parties can oppose the application. Registrants have the opportunity to argue that the USPTO should have considered their mark in the analysis of the application, and these oppositions go straight to the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB). - Cancellations

If a mark has registered that is too similar to the registrant’s mark, the registrant can begin a TTAB proceeding called a “cancellation” where they argue similarity, priority, or other deficiencies in the infringing mark. - Demand Letters

If the person using the infringing mark isn’t registering it with the USPTO, then the registrant of the original mark will have to reach out to the infringer separately and alert them of the original rights and federal trademark. This can escalate issues and alert others of competing trademark use and endanger the Registered mark if the infringer has priority. - Federal Litigation

The last resort for many registrants is federal litigation. This takes the case out of the USPTO/TTAB and into a federal courtroom. Federal litigation is the most costly option and can cost tens of thousands of dollars, but it is the most aggressive approach and can permanently stop an infringer from using a confusingly similar mark.

None of these filings are guaranteed to stop the infringing mark from registering. It is up to the USPTO examining attorneys, the TTAB, or the local courts to determine whether the marks can co-exist. However, it is a good way to make it known that the marks should not co-exist and that a registrant is actively policing the space.

Gerben IP can help you with your registered trademarks if you’re unsure about how best to keep your portfolio up to date.