The Complete Guide to Protecting and Registering Certification Marks

What is a Certification Mark?

When looking at almost any product and its packaging, consumers will likely find several symbols and/or words of certification. These symbols/words certify that the product has been given a “seal of approval” from various agencies or organizations.

For example, an electronic product that has been safety-tested by the organization UL might use display this symbol:

A product produced in an eco-friendly way that does not damage rainforests might display this symbol to show others it is Rainforest Alliance-certified:

There are many other “seals of approval” that products and services can use to show that they meet specific standards.

These are “certification marks,” and like trademarks, service marks, and other types of trademark protection, these marks can also be protected and registered with the United States Patent and Trademark Office to prevent others from creating confusingly similar certification marks. There are almost 8,000 live certification marks with the USPTO, and the owners of the filings know the value of protecting their intellectual property. However, unlike trademarks, certifications have special requirements unlike any other form of intellectual property protection, and it’s important to know what is being protected and how to protect it.

A Certification Mark Shows That a Product or Service Meets Certain Standards

A certification mark indicates that a product or service meets specific standards, such as the quality of goods and services, the region of origin for goods and services, or the group of people who provided the goods and services.

As a result, consumers use certification marks to make decisions about their purchases. Whether it’s buying products that are certified as eco-friendly, fair trade, or other certifications that align with the consumers’ beliefs and ideals, certification marks provide consumers with more information.

Many certification organizations go through thorough testing and review for the products/services they certify and, as a result, become trusted by consumers. Like trademarks, certification marks provide a shorthand for consumers. However, certification marks are different than trademarks in a variety of ways:

- They are used by a person other than the trademark owner

- They do not indicate a specific brand of the item

- They are not classified in the normal USPTO “classification” system

- They are not recognized in all countries where trademarks or service marks are recognized.

Some of the most common certification marks show that a good comes from a particular region. For example, since Idaho is known for potatoes, the Idaho Potato Commission (a state agency) wants to ensure that not just anyone can use the official “Genuine Idaho Potatoes” logo on their products unless they are potatoes from Idaho. Therefore, they registered this (and several variations) logo with the USPTO:

Another common use of a certification mark is to indicate quality or manufacturing. Certified USDA Organic is a standard set by the US Department of Agriculture and is associated with a logo that people have learned to trust. Producers of organic vegetables, meat, fibers, or foods have to meet stringent requirements to use this on their products.

Companies also use certification marks to show that their employees or associates have specific training and are given a certification of skill by a third-party organization. The labor or union marks can provide consumers with peace of mind that the person engaging in the activity is a skilled professional.

In fact, the oldest certification registration (registered 2/22/1949) currently registered with the USPTO is owned by a union to certify that printed products were made by union labor.

Certification marks are also frequently used products like cheese and wine to indicate that they meet the regulated standards to call their product a specific name. For example, the French Confederation Generale des Producteurs de Lait de Brebis et Des Industriels de Roquefort certify cheese that is made in a specific style and municipality.

Another certification mark likely seen by every adult movie-goer is the Motion Picture Association’s “R” rating, registered with the USPTO in 1993 (and in use since 1970).

Requirements for a Certification Mark

Unlike traditional trademarks, certification marks have unique requirements for ownership and registration:

- The owner is the organization that ensures and polices the quality or origin of the goods and services. These are organizations such as divisions of the US government, private companies, state governments, and union leaders.

- The owner does not sell the goods or provide the services that it is certifying. The integrity of the mark is based on the premise that the owner of the mark does not certify themselves and is an impartial third party determining the requirements of certification.

- The owner needs to ensure that the requirements to achieve certification are enforced and there is no unauthorized use of the mark. The USPTO will consider use by an unauthorized third party a lack of “legitimate control” and will not grant the registration or renewal.

The most important feature of a certification mark is “control” – one organization must have the ability to control the certification of goods and services to claim exclusive rights in a certification mark. Suppose they lose that control, and others are allowed to use the certification without meeting the standing set forth by the owner. In that case, the certification mark may cease to exist since all the consumer goodwill acquired is lost due to unauthorized third-party use.

Filing a Certification Mark

If a certifying organization wishes to register its certification mark with the USPTO, there are some unique challenges. First, when filing a typical trademark, it is classified into International Classes in accordance with the Nice Classification, a set of classes agreed upon through international treaty obligations to standardize trademarks across different countries. For example, clothing products are in class 25 whether an applicant files in the US, E.U., or Australia.

Certification marks, however, are outside of this classification. They are either Class A or Class B. Class A is used if the mark is certifying goods, and Class B is used for certifying services. For example, certifying organic foods would be Class A, but certifying organic farming methods would be Class B. One organization can own a mark in both classes as long as it ensures the quality of both the goods and services.

Another part of the filing process is to file “in use” or “intent to use.” In use means that there are people actively using the certification mark, and the applicant can provide proof of such. Intent to use means the applicant has not begun certifying individuals in their field but intends to do so and wants to secure rights. The intent to use application guarantees the applicant the earliest federal priority date while building goodwill in the mark and beginning the certification process with third parties.

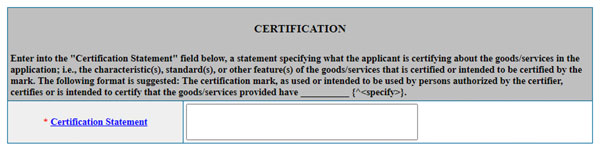

Certification mark applications also have a couple of additional requirements compared to regular trademark applications. The first is the Certification Statement, seen below. The applicant essentially explains what exactly the mark certifies – aka origin of goods, quality of goods, the union that made the goods, etc.

Risks of Certification Marks

Since certification marks, by definition, explain how something is made, where it’s from, or a characteristic of the goods or services, these marks are often deemed descriptive. However, this isn’t the death of the certification mark since marks such as USDA ORGANIC can get registered. Owners of certification marks have uphill battles to prove to the USPTO that the mark is distinctive to consumers and has a reputation worth protecting.

How to Use a Certification Mark

When proving the use of the certification mark, the applicant will not provide proof that they are using the mark, but instead, that third parties are using the mark to advertise certification. In the USDA Organic example, the US Department of Agriculture doesn’t provide photos of stickers. Instead, it shows that third-party farmers use the USDA Organic emblem on packaging, boxes, stickers, and advertising. Third-party use can look like a number of things:

- Tag lines, badges, or accomplishments listed on professional social media pages or websites

- Emblems, stickers, or printed packaging on the goods being certified

- Business cards advertising certification in a certain practice or profession

The most important part of any proof, however, is that it is not produced by the applicant. The USPTO will reject the certification mark if there is no proof that the mark is recognized within the industry as an indicator of quality, origin, or manufacturing.

Do you need assistance with a trademark matter?

Contact an Attorney Today