How to Respond to A Trademark Office Action

So, you filed your trademark application months ago and your new business has started on its way. You are eagerly awaiting to hear from the United States Patent and Trademark Office. After waiting for so long, you finally see an email from the USPTO, only to find out that the USPTO has issued an “Office Action” and your trademark has been denied.

The good news is that most USPTO Office Actions (a.k.a. the denial of your application) can be overcome. You have the option of filing a response to resolve the issues found and even talking to the examiner to find a way to get the application refused. This article will discuss exactly how you should respond to an Office Action.

What is an Office Action?

To get started, it is important to demystify the USPTO’s jargon. An “Office Action” is just an official action taken by the USPTO that stops your trademark application from moving forward. The severity of any given Office Action varies significantly.

For example, an Office Action could just be a “technical refusal.” This means that there is some technical problem (see below for examples) with your application that is preventing it from moving forward. These are relatively easy to fix (especially if you have a trademark attorney that knows his/her way around the USPTO). Other Office Actions could refuse your trademark due to another pre-existing trademark registration. These are more serious and difficult to work around. In a response to this type of Office Action, you would have to submit arguments and evidence to the USPTO to refute the refusal and explain why you believe your trademark should register.

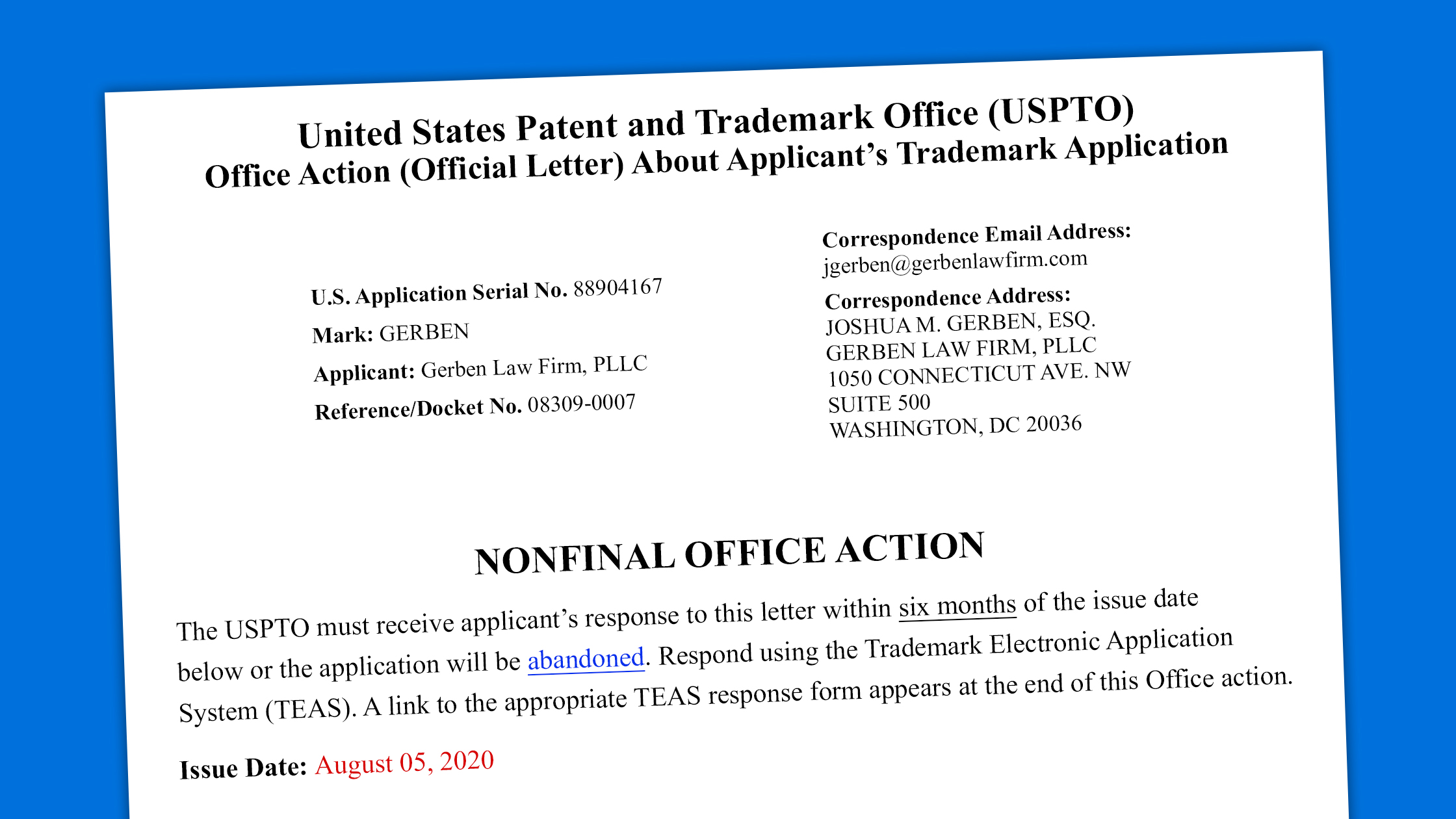

Moreover, there are actually two types of Office Actions:

- A NON-FINAL OFFICE ACTION

- A FINAL OFFICE ACTION

A “NON-FINAL OFFICE ACTION” is typically the first Office Action issued by the USPTO. Then, after receiving a response, if the USPTO refuses the trademark application again, it will issue a “FINAL OFFICE ACTION.”

Historically, you would have had six months to respond to either Office Action, however, a USPTO rule change in December 2022 now requires a response within three months. You can request a one-time three-month extension of time from the USPTO for $125 government fee.

Responding to Technical Office Actions

The USPTO issues technical refusals when they need the applicant to fix something technical in the application. Technical things can include clarifying what goods or services are in your application, disclaiming descriptive words in your mark, or giving a proper address, etc.

1. Fix Identification of Goods and Services

Every trademark application has an identification of goods or services, which the USPTO has divided into classes. For example, cosmetics are in Class 003, electronics are in Class 009, clothing is in Class 025, retail store services are in Class 035, and educational and entertainment services are in Class 041.

The USPTO has its own set of specific terms for goods and services that the application must use. For example, an application cannot simply put “clothing.” Instead, they have to list all specific types of clothing, such as “clothing, namely, shirts, pants, shoes.” Another example is “software.” The USPTO will only accept either “downloadable software” or “on-line non downloadable software” and the ID must describe what the software does. For example, “downloadable software for ordering food delivery.”

2. Disclaimer for Descriptive Wording

The USPTO will require you to disclaim descriptive wording. This means if you pick a word in your trademark that actually describes your goods or services, then that means the USPTO will not give you exclusive rights to owning that term.

For example, if Mozart owns a piano store and he wants to trademark “MOZART’S PIANOS,” then the USPTO will make him disclaim “PIANOS” because it wants to keep descriptive words like that open and free to use for the public.

But even if individual words in the trademark are disclaimed, if registered, the person still owns exclusive rights to the trademark as a whole. So even though Mozart has to disclaim the wording “PIANOS,” when he gets a trademark registration he still owns exclusive rights for the entire trademark “MOZART’S PIANOS.” He just does not own exclusive rights to use “PIANOS” alone.

3. Complete Ownership Information

The USPTO also has some technical ownership requirements that are not so obvious. For example, they will not accept PO Boxes as mailing addresses. So, they require an application to list a domicile address that they will keep hidden from public view.

Other examples include clarifying things about your business. Such as is your business a corporation or a limited liability company? Knowing the wide range of correct information needed in an application can save you a lot of time, energy, and money later down the road because it prevents a future refusal.

As seen in the next section, legal refusals are more difficult because they stem from legal issues.

Responding to Substantive Office Actions

The USPTO issues substantive refusals based on different laws stemming from the Lanham Act. These laws are meant to protect already registered trademarks, keep descriptive wording free and open to the public, and to advocate for entities to actually use their trademarks (instead of just trademark squatting).

1. Section 2(d) Likelihood of Confusion Refusal

When the USPTO decides that your mark is too similar to another registered trademark, it issues a Section 2(d) Likelihood of Confusion Refusal. This means that your mark sounds similar, looks similar, or overall has the same similar meaning to an already registered trademark. This law is meant to protect already registered trademarks because it stops similar marks from being registered.

For example, COCA-COLA, would not be too happy if the USPTO registered a trademark called KOKA-KOLA for soda. So, the most important consideration when you come up with a trademark name is to compare your name with already registered trademarks. The best way to do this is to do a trademark clearance search, which means you review the entire trademark database for similar names, review state trademarks, and then common law marks (names that are used but not officially registered).

When you get a Section 2(d) refusal, you will see there are two parts to a refusal. In the first part, the USPTO states why the marks are similar (i.e., KREST for toothpaste sounds too similar to CREST for toothpaste). In the second part, the USPTO explains why the goods and services are similar (i.e., KREST mouthwash is too similar to CREST toothpaste, because toothpaste companies almost always offer mouthwash too, etc). The USPTO has to explain why consumers would confuse the marks.

To respond to a Section 2(d) refusal, the best thing to do is to argue why your mark has a different overall meaning compared to the registered mark. This can be done in a lot of different ways, you can explain why your wording means one thing, while the other term means something else. For example, if your trademark is “SERGEANT PEPPERS,” you can explain that the meaning makes the commercial impression of music associated with The Beatles, while the wording PEPPERS just means food to the ordinary consumer. Another way you can respond is to argue why your goods and services are different from the registered mark’s goods and services.

2. Section 2(e)(1) Merely Descriptive Refusal

A Section 2(e)(1) descriptive refusal means that the USPTO thinks your mark just describes the types of goods and services you are offering and they want to keep that wording free and open to the public to use. For example, if you wanted to trademark “CHOCOLATE CHIP” for ice cream, the USPTO wants to keep the wording “CHOCOLATE CHIP” free to the public, so all different types of ice cream companies can use the wording chocolate chip to describe their flavors.

The best way to avoid a descriptiveness refusal is to make up fanciful words or use arbitrary names that do not seem connected at all to your goods and services. The USPTO considers these types of marks as suggestive, meaning a person has to think a little bit more about what the name is and it is not so obvious from the name.

For example, before these terms were well-known, when you see or hear “CHERRY GARCIA” or “TONIGHT DOUGH,” you do not immediately think of ice cream. But Ben and Jerry’s came up with these creative names to use as ice cream flavors. If you started your own ice cream company today, you would not want to try to trademark just “COOKIE DOUGH” because that is descriptive. Instead, a good strategy would be to make up a name that has a double meaning, such as “DOUGH-DOUGH BIRD.”

3. Specimen Refusals

To get a trademark, you must show the USPTO proof that you are using your mark. This can be done in many ways, such as providing pictures of your goods with the label on them or providing a screenshot of your business website.

The USPTO has many different technical requirements when they review a specimen. If your specimen does not show the trademark in the way the USPTO needs to see it, then they will refuse your application. They do this because they want to make sure that everyone who gets a trademark registration is actually using the trademark. This prevents trademark squatters.

For goods, the best way to get your trademark approved is to take photographs of your goods with the label on them. For example, if your goods are peanut butter, you just need to show a photo of the jar and the label of the peanut butter on the jar. If you want to trademark your restaurant services, you provide a screenshot of your restaurant website where you have your restaurant name at the top of the webpage.

Sometimes the specimen refusals are technical and based on certain USPTO rules and regulations. For example, a common type of refusal happens when people try to trademark clothing. Generally, people will submit a t-shirt with the trademark name on the front of the t-shirt. For example, if Nike tried to register the mark “JUST DO IT,” they cannot just give a picture of a t-shirt that has “JUST DO IT” on the front. The USPTO considers this a design and not a trademark. Instead, Nike has to send a photograph of the clothing hang-tag, where it has the “JUST DO IT” logo on the price tag. The USPTO considers this trademark use. Someone not familiar with the trademark process would not likely know this.

The best way to prevent a specimen refusal is to hire and consult trademark attorneys for getting your proof ready. Specimen refusals take up a lot of time and slow down the trademark process, it is best to try to avoid them altogether so you can get your trademark as fast as you can.

Final Thoughts

While an Office action refusal stops your trademark application, it is not the end of the road for you. There are best practices and legal strategies you can use to fix trademark applications, in order to convince the USPTO that your mark deserves a trademark registration!

To save the most time, energy, and money upfront, it is best to get trademark counsel before applying for a trademark. That way, you get the most complete information needed to move forward with your trademark idea, you can assess all the risks, and you know what challenges if any, are to come up if you really want to get your trademark.

Here at Gerben IP, we are happy to get started and help you on your way in responding to Office Actions and achieving your trademark.

Do you need assistance with a trademark matter?

Contact an Attorney Today